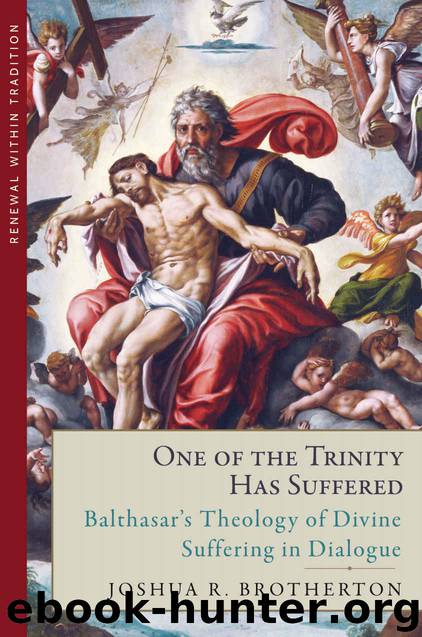

One of the Trinity Has Suffered: Balthasar's Theology of Divine Suffering in Dialogue (Renewal Within Tradition) by Joshua R. Brotherton

Author:Joshua R. Brotherton [Brotherton, Joshua R.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Emmaus Academic

Published: 2020-01-16T16:00:00+00:00

For Balthasar’s Trinitarian (ur-)kenosis, see, for instance, TD III, 188 [G 172]; TD IV, 323–331 [G 300–308]; TD V, 243–246 [G 219–222]. Concerning the “kenosis” of the Holy Spirit, see TD II, 256, 261 [G 232, 237]; TD III, 188 [G 172]; TD IV, 362 [337]; A Theological Anthropology, 73 [G 94]; see also Jeffrey A. Vogel, “The Unselfing Activity of the Holy Spirit in the Theology of Hans Urs von Balthasar,” Logos: A Journal of Catholic Thought and Culture 10, no. 4 (Fall 2007): 16–34.

Steffen Lösel, however, correctly notes: “Although Balthasar refers at times to the Spirit’s experience of suffering, he emphasizes that the Spirit only reflects the passion of the Son. He emphasizes that ‘we cannot state a kenosis of the Spirit’s freedom’ (Hans Urs von Balthasar, Theologik, vol. III, Der Geist der Wahrheit [Einsiedeln: Johannes Verlag, 1987], 218). Cf. also idem, Theologik III, 188; idem, Pneuma und Institution. Skizzen zur Theologie IV (Einsiedeln: Johannes Verlag, 1974), 264ff.” (“Murder in the Cathedral,” 438n64).

Late in his career, Balthasar states: “we clearly see the Son’s ‘economic’ death as the revelation, in terms of the world, of the kenosis (or selflessness) of the love of Father and Son at the heart of the Trinity. As we have shown, this is the precondition for the procession of God’s absolute, non-kenotic Spirit of love” (TL III, 300 [G 276]).

121 See his Church Dogmatics I/1, The Doctrine of the Word of God: Part 1, trans. G. W. Bromiley and T. F. Torrance (New York: Continuum, 2004), xiii.

122 See, e.g., Church Dogmatics IV/2, The Doctrine of Reconciliation: Part 2 (New York: Bloomsbury, 2004), 59. Nonetheless, he also expresses agreement with Patripassianism (see Church Dogmatics IV/2, 357). Balthasar sees a problem with Barth’s reluctance to impose the events of the passion onto the internal life of God, in effect separating the processions from the missions (see TD V, 236–239, 243–246). I agree with David Lauber’s assessment that Balthasar veers closer to Moltmann than he should in critiquing Barth, whose modesty should serve as a corrective for Balthasar (see “Towards a Theology of Holy Saturday,” 344).

123 See Church Dogmatics IV/1, The Doctrine of Reconciliation: Part 1 (New York: T&T Clark, 1961), 193. For an appreciatively critical appropriation of Barth’s Trinitarian theory, see Thomas Joseph White, OP, “Intra-Trinitarian Obedience and Nicene-Chalcedonian Christology,” Nova et Vetera (English Edition) 6, no. 2 (2008): 377–402. For a refutation of the idea that humility may be properly applied to God, see also Guy Mansini, “Can Humility and Obedience be Trinitarian Realities?” in Thomas Aquinas and Karl Barth: An Unofficial Catholic-Protestant Dialogue, ed. Bruce L. McCormack and Thomas Joseph White, OP (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2013), 71–98.

Mansini, therefore, rightly criticizes Balthasar for “[imagining] the Son ‘offering’ to become incarnate and the Father being ‘touched’ at this offering” (“Humility and Obedience,” 96). But he does not capitalize upon Thomas’s words that “for the Son to hear the Father is to receive his essence from him” (97, citing Super Evangelium S. Ioannis Lectura, no. 2017).

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(6502)

Why I Am Not A Calvinist by Dr. Peter S. Ruckman(3780)

The Rosicrucians by Christopher McIntosh(3067)

Wicca: a guide for the solitary practitioner by Scott Cunningham(2714)

Signature in the Cell: DNA and the Evidence for Intelligent Design by Stephen C. Meyer(2513)

Real Sex by Lauren F. Winner(2496)

The Holy Spirit by Billy Graham(2440)

To Light a Sacred Flame by Silver RavenWolf(2366)

The End of Faith by Sam Harris(2306)

The Gnostic Gospels by Pagels Elaine(2047)

Nine Parts of Desire by Geraldine Brooks(2014)

Waking Up by Sam Harris(1970)

Heavens on Earth by Michael Shermer(1963)

Devil, The by Almond Philip C(1913)

Jesus by Paul Johnson(1900)

The God delusion by Richard Dawkins(1863)

Kundalini by Gopi Krishna(1833)

Chosen by God by R. C. Sproul(1776)

The Nature of Consciousness by Rupert Spira(1699)